A quick history of security in the United Kingdom

The British security industry – in the sense of a publically recognised body of private firms providing protection against crime – emerged between the late 18th and mid 19th centuries. At this time, the industry was composed largely of the leading lock and safe firms, which, in contrast to the long-established small lock-making workshops, exploited largescale factory production.

These firms developed the first security brand identities, and some maker’s names (notably Bramah and Chubb) became closely associated with the promise of ‘perfect’ protection against crime.

Furthermore, these companies pioneered innovation in security technologies, and thereby established a link between brand-name security and cutting-edge design.

19th Century - origins

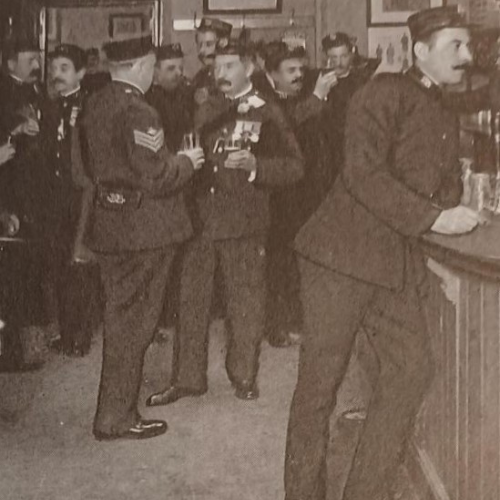

The 1850s saw the formation of the Corps of Commissionaires (now Corps Security), in the wake of the Crimean War, as a voluntary organisation to find employment of ex-servicemen. They did various jobs, but some had a security function, including acting as doormen, or on reception, at shops, offices and later cinemas in London and beyond. There were about 3000 commissionaires by the early 1900s, making them by far the largest private security body of the time. They had royal patronage and broad official support and approval.

Besides commissionaires, security guarding duties were mostly undertaken by night watchmen, employed usually directly by private companies, though sometimes shopkeepers for example might pool resources to subscribe for a watchmen to patrol their street after dark.

Watchmen were often expected to patrol the premises after dark, sometimes using watchmen’s clocks to log their rounds. They were not highly regarded, and some at least were elderly and fairly useless for protective purposes – though others responded pretty vigorously to incidents.

1930s - development of private industry

The first commercial private security operations in England started to develop from the 1930s. They were very small night watching and guarding operations, serving major urban areas, offering services both to industrial/commercial and to residential subscribers.

Their uniformed and disciplined appearance caused some concern at a time that was marked, in the UK as elsewhere, by the formation of paramilitary organisations.

By this time, even before the First World War in some cases, the larger industrial and commercial companies had somewhat better organised internal security operations, often called ‘works police’ and sometimes closely modelled on police constabularies.

Sometimes employees of works police were even sworn in as constables by the local chief constable, giving them the wider legal powers reserved for police.

1940s post war expansion

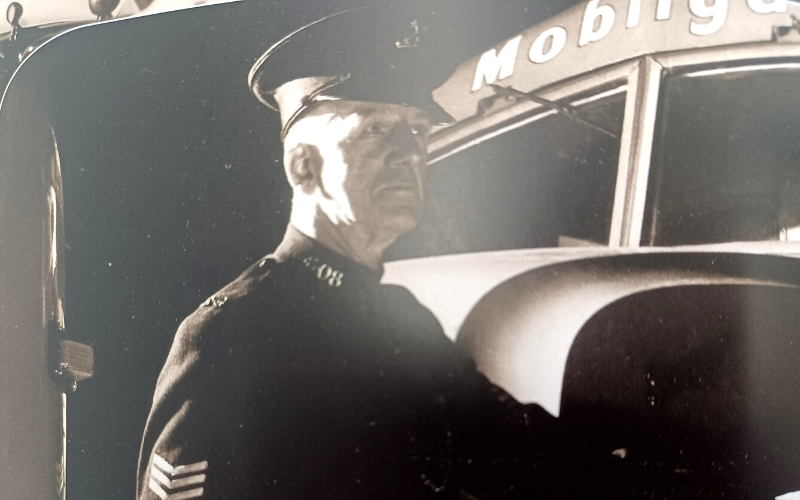

Security guarding operations expanded considerably after the Second World War, including the formation of what would become the major players in the industry (including Securicor and Factoryguards, later consolidated as part of Group 4). Major areas of work were guarding (static or mobile) and cash-in-transit, the latter growing in the shadow of increasingly daring and professional robberies from the 1950s. Again, some suspicion attached to what were often referred to as ‘private armies’, and especially the potential for criminal infiltration or political coercion which they seemed to present.

There was also concern about guard dogs following attacks (including on children) by unsupervised dogs, leading to the Guard Dogs Act 1975, the first legislation to regulate any aspect of the security industry.

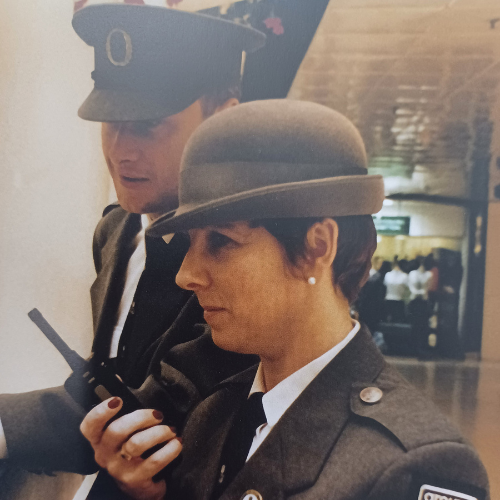

The Home Office and police fretted about the similarity between security and police uniforms, though the major companies (Securicor, Group 4, Security Express) sought to distinguish themselves and thereby (and in other ways) to foster close relations with the police. Close association with the police was seen as a selling point for security companies, but was also valuable in opening up opportunities for police vetting of security officers.

This was rarely formally offered, though informally it probably did take place in some places. Recruitment into security companies was carefully managed in the larger companies, with much emphasis on character references, searching interviews, even sometimes fingerprinting.

Smaller companies were often seen as more disreputable, and there was a perception of extensive crossover in parts of the industry between security and criminality (with occasional cases exposed). Numbers of security employees – most of them employed in-house – rose considerably from about 67,000 in 1951, to 130,000 in 1971, to almost 160,000 by 1991.

1960s - drive for professionalism and formation of the BSIA

From about 1960 there was a growing effort to improve professional standards in security. This was formalised in technical areas through the development of British standards in various areas (e.g. intruder alarms, security glass, safes and cash protection). In manned services, it followed the formation of professional associations such as IPSA (founded in 1959 as the Industrial Police and Security Association), and the publication of professional handbooks in security practice and management (e.g. Oliver and Wilson’s Practical Security in Commerce and Industry, first published 1968).

The British Security Industry Association (BSIA) itself was established in January 1967 with similar objectives, and to provide a medium for dialogue between central government and the security industry (the major players originally included Securicor, Group 4, Security Express and Chubb). Government and industry also came together through the Standing Committee on Crime Prevention, established by the Home Office in 1967 as a government-industry-trade union committee that sought to take forward crime prevention activity in private industry, and on which security companies were represented.

1970s into the modern age

The period from the 1970s saw continual growth in almost all areas of security. While the traditional lock and safe business started to wane, there were major developments in alarms, large growth in both contract and in-house security (boosted in some respects by government out-sourcing), and the development of new lines of business including CCTV. It remained a politically contentious subject, including around privacy protection and the work of private investigators (partly the focus of a major government committee in the early 70s), and around the growth of false intruder alarm calls and moves towards de-listing/non-response from the police.

A movement also developed for regulation of the industry, led publicly by Bruce George MP but backed by some of the major security companies too, though resisted in the 70s and 80s by the Home Office. Efforts at self-regulation continued and were stepping up in the 80s, including through the BSIA.

Ultimately resistance to statutory regulation gave way in the 90s and eventually delivered in the Private Security Industry Act 2001.

With many thanks and acknowledgement to Dr David Churchill, School of Law, University of Leeds